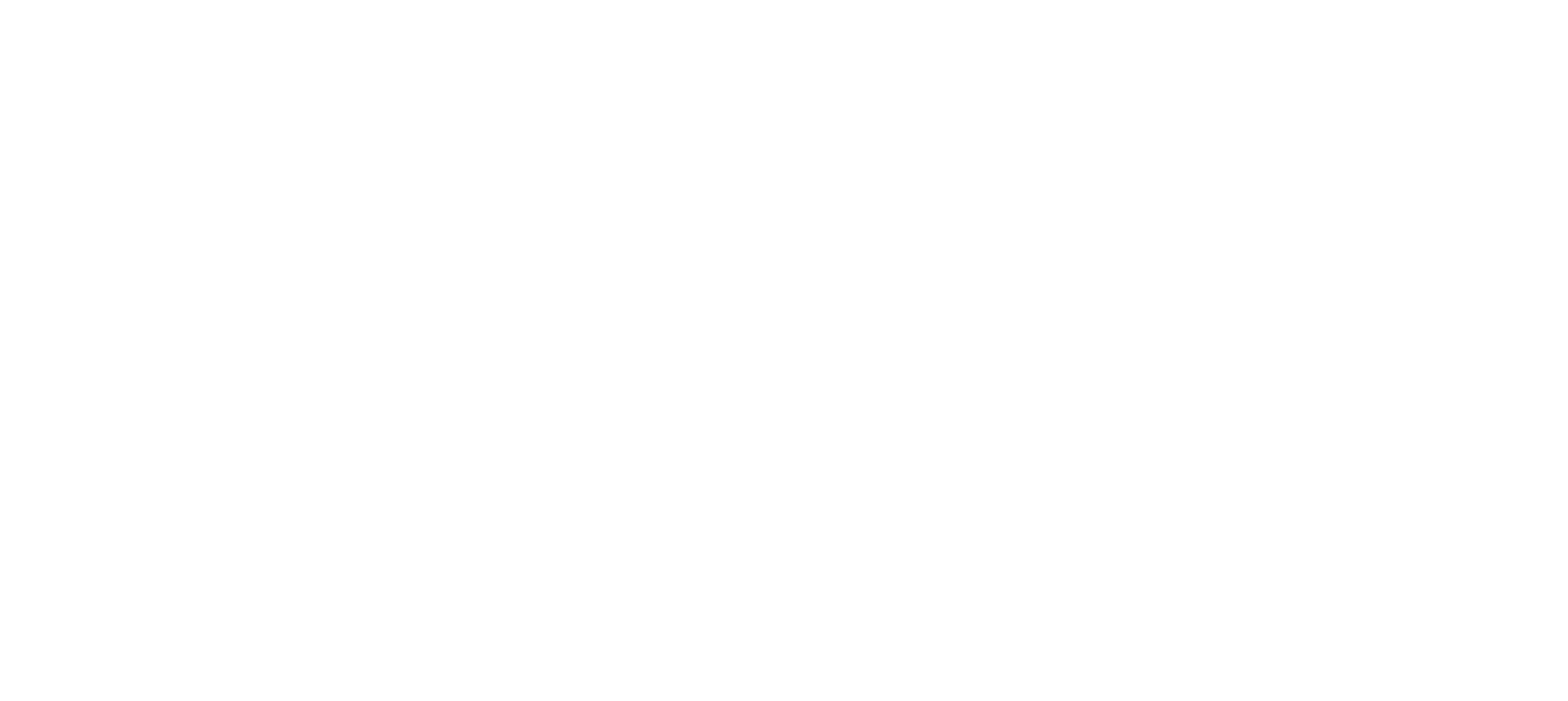

Coconuts are floating seeds and are very effective at moving on ocean currents between islands.

Coconut palms are one of several plants that were both native and introduced to Polynesia. Coconuts are floating seeds and are very effective at moving on ocean currents between islands and establishing themselves there. Archaeological studies in 2015 on Moorea settled a long-termed debate about whether coconuts had made it to these islands on their own by finding ancient coconut shells in an excavation that were below human-related material. So coconut palms are native, but they were also such an important plant for Polynesians that they were hybridized for multiple uses and carried on voyages of settlement across the Pacific. New varieties were introduced by the Polynesians as they settled islands and gradually the native variety disappeared.

Polynesians and other tropical island peoples used coconuts for food, drink, and to produce a high-quality oil. In the mid-nineteenth century coconut oil was discovered by the western world and created a boom in coconut farming. Copra is the dried meat or kernel of the coconut and this was the product that was produced on the islands and sold and shipped around the world to be crushed into fine oil that was used in a variety of products including soaps and cosmetics. The business was lucrative enough that almost every open, flat piece of land throughout the tropical South Pacific was planted for copra. The motu of high islands and atolls were perfect sites for these plantations since there was not much else of commercial value that could be grown there.

making copra

Eventually in French Polynesia plantations covered virtually all of the larger motu throughout the Tuamotu Archipelago, and on the reefs of the Society Islands. By the 1860s the chiefly family that controlled Tetiaroa started planting coconut palms across the island.

Prior to the plantations, and prior to the arrival of people, the motu of Tetiaroa would have been covered by a variety of native trees including, Pisonia grandis, Calophyllum inophyllum, Thespesia populnea, Guettarda speciosa, Morinda citrifolia, Hernandia Sonora, and dense understory of Scaevola, etc. These trees and native ground cover would have provided excellent nesting sites for the millions of seabirds that called Tetiaroa home.

Guettarda speciosa / Kahaia

Hernandia nymphaeifolia / Ti'anina

Pisonia Grandis

Thespesia populnea-Amae / miro

Tournefortia Scaevola & Suriana

Calophyllum inophyllum

Coconut palms would have been there as well, but before people arrived, they would have mostly occupied a band close to shore where the nuts were deposited by waves. And because coconut palms do not have useful branches, they were not used by birds for nesting.

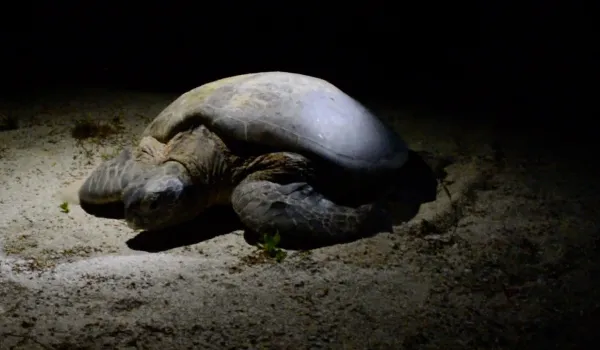

With the arrival of the Polynesians, native trees would have been thinned and coconut palms would have been planted near habitation sites, but they would still have been only a small percentage of the flora. As more people moved to the island, habitation and ceremonial sites expanded, and seabird were displaced and eggs were collected, the bird populations would have dwindled. But when copra production became the focus, everything changed. Native trees were cleared to plant rows of coconut palms and understory vegetation was removed so that the coconuts could be collected easily. There were no plants left for the birds to use for nesting or cover.

Motu covered in coconut palms.

Motu Oroatera in 1955

Tetiaroa was used for copra production from the 1860s right up into modern times. In aerial photos from the 1950s rows of coconut palms are visible with few if any other trees. Birdlife on Tetiaroa would have been at a low point at that time. In 1966 however Marlon Brando bought the island and stopped copra production, and the island’s forests, and the bird populations, began a period of slow recovery.

Fast forward 55 years and we are now planning to remove rats from the island and grow the bird populations back. Native trees have been able to grow back around the margins of the motu and in some places in the interior where senescent coconut palms fall and create gaps in the canopy. On Motu Reiono, a Pisonia forest has been able to establish itself, likely aided by coconut palm removal by storm waves. But we will have to actively remove coconut palms across the island and grow native trees if we want to give the birds a chance to come back.

Return of the Pisonia forest