The evidence is clear - coral reefs are under stress globally. It is also well known that ecosystems such as coral reefs are made up of thousands of component organisms that impact each other in complex ways we are still working to understand.

From 2007 through 2009 the predatory starfish commonly known as the 'Crown of Thorns' (Acanthaster plancii or taramea in Tahitian), devoured the coral reefs of Moorea and Tetiaroa. Up to 90% of the coral on the outer reef slope were eaten.

This occurrence is a natural one, where the starfish population explodes for some reason and they all eat coral until there is no more to eat, and then the starfish population dies back.

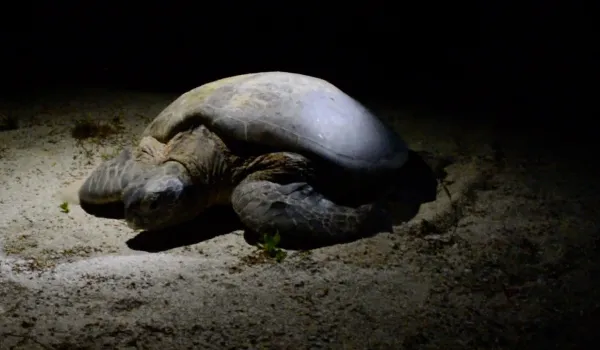

Then in 2010, a cyclone struck the islands and physically broke the reef up, dislodging dead coral and flattening out the reef structure. This also was of course a natural event. However, the climate crisis is changing the natural order of these events. Scientists predict that, with warmer climates to come, the frequency of cyclones will increase, as will coral bleaching which also decimates reef corals.

After the Acanthaster outbreak and Cyclone Oli, the coral reefs on Tetiaroa and Moorea were in very bad shape. Everyone wondered if they would recover. Scientists from the Long-term Ecological Research program (LTER), working at the UC Berkeley Gump Research station, decided to use this as an opportunity to see how a coral reef responds to a major stress like this.

What they found now informs fishery decisions in these islands.

The LTER scientists found that coral larvae, still abundant in planktonic form, were trying to settle on old dead coral surfaces, but brown algae was settling faster.

Soon most of the surface of the dead reef was covered with algae, blocking the return of coral to the system. This same process resulted in coral reefs in Jamaica shifting to algal reefs and destroying the fishery and tourism businesses. Everyone was very worried that that might be the case here.

But then, presumably because these islands still have a robust fish population, the herbivorous fish species with plenty of algae to eat, began to multiply. Their populations grew until they ate up most of the algae and created space for the coral larvae to settle.

And the coral came back. The system slowly shifted until the outer slopes of the reefs on Tetiaroa and Moorea were covered with tiny corals.

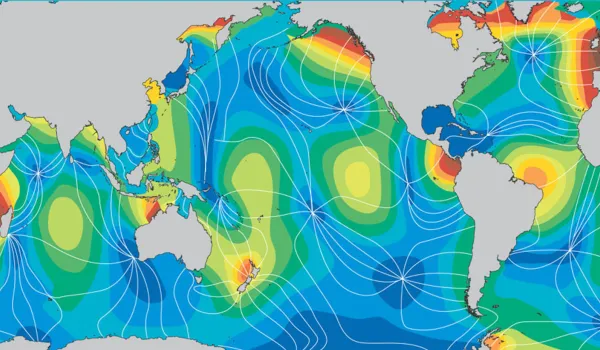

graphic: Moorea Coral Reef LTER

Naso unicornus | photo:reeflifesurvey.com

Naso hexacanthus

Scarus globiceps

Scarus rubroviolaceus | photo: Mark Rosenstein

Scarus rubroviolaceus

The key to the recovery of the reefs was a healthy fish population, particularly the herbivorous fish like Surgeonfish and Parrotfish. These also happen to be the species that local people like to eat the most, so it raises a problem.

When this dilemma was discussed with a local elder, Papa Mape, he said that when he was growing up the community’s response to a taramea invasion was to stop fishing in the lagoon completely, relying only on pelagic (open sea) fish and allowing the lagoon fish population to aid the reef in recovery. In present times, with the local population three times what it was when Papa Mape was growing up, it is not so easy to control a fishery like this.

Tetiaroa Society’s 2020 Fishing Report shows that it is exactly these key herbivorous fish that are being targeted for capture by fishermen. A full 70% of the fish taken from Tetiaroa fall into this category and 50% are just one species. This leaves the coral reef of Tetiaroa vulnerable to major stress events. Keeping our ecosystems healthy is one of the best ways to prepare for climate-related changes to come and this means working to understand our marine ecosystems and then regulating our impact on them.

For more information on the Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) Project:

Read the paper & visit the LTER site.